Click this link for access to a free Family Wealth Education Institute class on advanced estate planning and estate tax control/elimination personally taught by Dr. Camarda & “Super Board-Certified Tax Lawyer” John Crawford.

Executive Reading Tip

There is a lot of material in this report, and it has been my pleasure to research and prepare it for you. Still, if you are like me, you may not have time to page through the whole thing, and may prefer “news you can use” to put to work right now. If you are that kind of reader, may I suggest you focus on the “Case Study” boxes which are derived from Portfolio Stress Tests we did for folks who might look just like you. The conclusions are often scary (we find this a lot) but the lessons are very valuable. The case study material is very typical of what we usually find when we do these stress tests, and it’s a very efficient way to see the practical applications of the material in this report, and to focus on key problem areas that may be lurking in your portfolio and costing or risking you big money. These are not unusual cases at all, but very typical of what we find – chances are good that one or more of these problems may be lurking in your own portfolio, and we would be very happy to give you a free second opinion/checkup to see.

For you fast readers, the headings for the case study and other compressed material (like checklists and summaries) are in red, so you can find them quickly as you flip through.

Third Edition Key Points

- Are you overexposed to high risk “conservative” investments?

- As this report is written, we believe that bonds, and US large cap “blue chip” stocks – both of which are traditionally considered conservative- may be at higher risk of significant losses now. When we do Portfolio Stress Tests, we are finding what we believe to be too much of these investments held by many new folks who ask us for a second opinion.

- Are you positioned to profit from the new “hot sectors?”

- Because of the conditions in 1a above, many investors lack exposure to key asset classes such as foreign and emerging markets – one of which (China has gone up nearly 20 times more (about 40% vs. about 2%) the Dow Jones Industrial Average so far this year.

- Do you know how to find hidden fees that may be cutting your returns?

- This is very easy but extremely tedious. There’s more detail below in the report, but the gist of it is you often have to wade through reams of disclosure material – prospectuses, account application forms, contracts, prospectus supplements, annual disclosure books, statements, the back of confirmations (often written in code and printed in feint ink), and so on to pull out the raw data, then assemble and compile it into a composite to really see what’s going on. Many suspect this process is made intentionally difficult to keep consumers in the dark on real costs, and it seems like many of the advisors who sell these products haven’t read all the material, and hence don’t really appreciate how high total costs can go, either.

- Are the wrong investment set ups causing you needless taxes?

- This can be a real problem, as we get into below. Annuities can be ticking tax time bombs with some of the highest tax rates around. Putting capital gains assets in IRA’s can nearly double the tax rate – needlessly for – some folks. Tax finesse can pay real dividends, and the lack can be almost disastrous. See the Case Study under Danger #9 for more detail.

- How to find out if you’re really getting the returns you think you are…

- Ask if your investment adviser has the ability to calculate internal rates of return and time weighted returns, net of all fees and costs, and request this if they do. This gives the clearest picture of actual performance, but unfortunately many advisors do not provide this, and sometimes provide statements that are confusing or misleading. If this is the case, take us up on our FREE Portfolio Stress Test and we will help you to evaluate what your performance has been, and compare it, if possible, to the market averages such as the S&P 500 (see the Case Study under Danger #6 for an example).

- Action steps to take now to protect from the next market downturn

- We believe the world is in a long term bull market, but that performance leadership has shifted from US large caps (“blue chips”) to other asset classes; please see detailed information under Danger #2. Bondholders – who we believe may be at high risk of significant losses – should read Danger #8 very carefully.

- Tips to increase retirement cash flow, income & security of not running out!

- This is a complicated one, but retirees should know that most recent research indicates that a significant percentage of investments in stocks is critical to increasing the probability of achieving the growth needed to maintain income over the life span. At this point in the bond market cycle – we see a long decline coming for bonds – equity income – dividend paying stocks, covered call writing strategies, etc. – looks to be a better bet than fixed income, at least until interest rates go up and bonds become cheaper again. Finally, you may want to consider so-called “longevity insurance” which would allow a deferred pension that kicks in later – like when you may run out of money if you live long – and then pays you for life; these can be much cheaper than buying immediate annuities now. Still, as for bonds, we counsel waiting until rates go up before committing yourself to annuity type products. Take us up on the FREE Portfolio Stress Test for more personalized information.

Introduction: Facing and Managing Investment Danger

The dangers facing today’s investor have never been more deeply felt.

The bloody lessons of 2008 left no investor untouched, but some weathered the storm far better than others, and instead of facing financial desolation, are looking forward to continued prosperity now, and in the years to come. If you stuck to your guns and avoided the temptation to sell into the bear market or flee for the imagined safety of bonds, annuities, or bank cash, I salute you.

Which camp are you in? For as painful as the Great Crash of 2008 was, it will not be the last one. And as the market has rebounded sharply from the March 2009 lows, it is only natural to have forgotten the lessons of the Great Crash, to have become comfortable as the post-2008 rising market – one of the longest bull markets ever in the US – continues to soar, and maybe to let our guard down a little as we go with the flow.

A lot of people felt that way in the months before 2008 changed everything for modern investors.

We be racing toward another such inflection point, as “US large caps” – the kind of stuff that’s in the S&P 500 and dominates many investors’ accounts, maybe yours – have floated from deeply undervalued to fairly valued to maybe overvalued and primed for a correction or bear market.

As we face an ever-uncertain future, knowing how to control investment danger can make all the difference between staying on the path to prosperity, and facing a bleak and impoverished retirement.

At this point in time, we feel one of the greatest dangers is an overconcentration to US large cap stocks, which may be due for a correction or bear market sooner than many investors may want to believe. On the other hand, other asset classes with significant profit potential may be underweighted or totally absent from investors’ portfolios, sharply increasing risk and reducing profit potential. Later in this report you will have the opportunity to request a no-obligation portfolio review to help you assess these risks for yourself.

This report summarizes basic measures that each investor would be wise to consider to evaluate and guide their investment planning. It can also be extremely useful in flagging danger signs before catastrophic losses become, perhaps, unavoidable. As such, it is intended as a diagnostic tool, to guide the practiced eye toward those indicators which may warn you that something may be amiss, and help you take corrective action while it may still be relatively painless to do so. While helpful, these guidelines are by no means foolproof. Still, they can uncover danger signs you really should address, which could make a very real difference in your financial health.

This report on the 9 Dangers Facing Today’s Investor™ can be used on two levels. The first is your application of the basic understanding that you will gain from the material you read here to your own investment situation. This alone is certain to raise many questions, and even a bit of probing on your own can help you a lot. The second level is through the free offer of professional service you will learn about as you go through this report. You will have the opportunity – at no cost or obligation – to have some of the tests described here actually conducted on your portfolio, by a trained and licensed investments practitioner, using professional analytic evaluation techniques. We call this a Portfolio Stress Test™.

What’s a “Financial Stress Test”?

Stress testing is a way to model how a given system – like the portfolios on which you rely for financial security – may behave when conditions become unfavorable. Systems like your computers or the electrical networks that power your house may work fine under many circumstances, but break down utterly when things change. Computers crash, breakers blow, and sometimes wires melt with disastrous consequences. A metal component – shiny and flawless to the naked eye – may seem perfect, but in fact be riddled with internal flaws and microscopic cracks which could cause it to crumble, even under the loads for which it was designed. Also true for the heart which pumps oxygen and nutrients to your brain and body, the wheels on which you ride or the plane in which you fly, and the nest egg on which you depend for the money you need to live and accomplish the things you want and dream about.

A stress test applies “what if?” conditions to a system, and considers what might happen. An important point is that these “what if?” conditions are generally not extreme ones. They are the kinds of things that can be reasonably expected to happen sooner or later, that the system was – or should have been – designed to control. New Orleans’ tragic experience with Hurricane Katrina is a good real-world example of a deeply flawed system crushed by real world stresses when they finally came into play. It is important to note that had New Orleans’ water control systems been stress-tested and fortified before Katrina, much damage, cost, and misery could have been avoided. The fallacy of expecting mud walls to hold hurricane-force flooding was entirely predictable and correctable, had it been addressed in advance.

In the world of portfolio construction, sadly, many of these entirely predictable conditions are routinely overlooked by both the marketers and buyers of investment advice. Everything on your statements may look bright and shiny and fine, until a 9-11, technology bubble, housing bubble, 2008 “black swan”1 event, “flash crash,” or something else yet unanticipated hits the weak points, the system crashes, and your wealth oozes out into the mud, perhaps to never be reclaimed.

This report is intended to help alert you to the hidden dangers that have be burrowed into your portfolio, giving you a chance to take corrective action before encountering the kind of catastrophic conditions that could devastate your financial security.

The 9 Dangers Facing Today’s Investor™ – the parts you can do on your own, and the parts you’ll get a chance to have a licensed practitioner conduct at no cost or obligation – is designed to help you discover if some of these “stress cracks” are lurking, unseen, in your own portfolio, just waiting for the right conditions to unleash devastation on your retirement, and peace of mind. And rest assured, 2008 was by no means the last killer storm you will face. Worse yet, the “safe” strategies many investors – and their advisors – have adopted in reaction to ’08 may wind up looking like those mud walls in old New Orleans…bright with whitewash on the outside, but ready to melt away into the river once the wind really starts blowing. If you suspect you may be one of these people who went into a “new, safe strategy” after the last Great Crash, pay particular attention to Dangers 2, 4, 5, & 8.

Danger #1: Will You Run Out of Money?

This is a pretty important point of interest, isn’t it? All seems well while your account balance seems high and the checks keep flowing, but will it last? Many factors impact this. Will rates of return keep up with your needs, and with taxes and inflation? Could another market crash whittle that fat account balance down to something much leaner? Are you spending far too much, so that you will run out of money even if you get miraculous rates of return…which you probably won’t? How long will you and/or your spouse live, and need spending money? People are living far longer now, and this so-called “longevity risk” is starting to affect millions of people. What about unseen health care costs? Long-term care? Do you have big projects in mind, or want to leave money to your family or charity? Will Social Security and Medicare be there for you always, even as the projections predict they will both run out of money not too far down the road? Will or have you claimed the right Social Security payment strategy? This decision is counterintuitive and complicated (call us if you would like some free help), but the wrong choice could literally cost you hundreds of thousands of lost income over your retirement. All these factors can add up to an extremely complicated (and hard-to-predict) model, but the comparatively simple math of estimating your after tax-and-inflation cash needs, then assessing the staying power of your pool of capital, assuming reasonable rates of return, can and should be done on an annual basis, to get a good feel for how well you’re tracking that endlessly moving target. If you haven’t done this lately, you need to. Learn the math, get out that financial calculator, muddle through a decent web site, to help you determine how rosy your retirement picture is, and what changes might bring you more security. Keep reading, the other “dangers” provide some keys to this puzzle.

Case Study Businessman

We begin with a very typical case. “Fred” is 56, has about $900,000 saved in various investment accounts, including IRA’s, a 401K, and a regular taxable account, and wants to retire in 9 years on $120,000 (before taxes) in today’s dollars to support the lifestyle he wants, and to maintain $120,000 in purchasing power. His assumed life expectancy is 85, but longevity runs in his family and with medical technology advancements he may life much longer. He expects to begin taking Social Security of $42,000 at 67, and will get a deferred compensation payout from his employer of $59,000 from age 65 to age 71. He must make up the difference from his savings.

Assuming a reasonable rate of return and some market volatility, but no 2008-like market plunges, his money is predicted to peak at some $2,000,000 at age 71 (The year his deferred comp runs out) but be completely exhausted by the time he is 83 – a few years before his assumed life expectancy, and perhaps many years before his actual life expectancy. Throw in unexpected health care costs or the need for long term care, and we have a real crap shoot on how long before the money’s gone.

Of course, there is no assurance of the money lasting even to 83. Depending on how much he actually spends, what taxes are, and probably most importantly, how well he makes investment decisions (or who he uses for portfolio advice!), his money may last longer – or be gone far sooner. According to the “Monte Carlo” analysis we did for his Stress Test, his money may last until 93 (very unlikely), or be gone by 79. The median probability is for exhaustion at 83. Overall, he has a little less than a 50-50 shot at realizing his goal of target retirement income until age 85.

A coin-toss, pretty much.

Not what he wanted to hear, but what he needed to know.

The point, of course, is that it’s pretty much impossible for Fred to determine this on his own. He has almost a million bucks, is still working and saving, and has a rich deferred comp plan and a high Social Security benefit to look forward to.

Is it easy for Fred to look at his situation and believe he has plenty of money. But, as you can see, the reality is far different, and if he makes some of the mistakes you’ll read about below, he could be in real danger of running out of money very young, or having to work until he drops or can no longer find work.

Danger #2: Is Your Portfolio Riddled With Unseen Risks?

Is your portfolio setting you up for the next crash? Judge not a book by its pretty cover, the load capacity of a cracked piece of steel by its fresh coat of paint, or an investments plan by the slick graphs and marketing materials. Ask any NASDAQ investor, whose circa-1999 “conservative” portfolio, “well-diversified” over dozens (or hundreds) of “blue-chip” companies lost most of its value between 2000-2003, and ten years later was still only worth about half of its value in 2000. In fact, it took some fifteen years for NASDAQ to show a glimmer of a profit – an annualized rate of only 1.5% before taxes and inflation – a long, scary, heartbreaking fifteen years, that no doubt left many broken wallets along the way. The combination of decimated values and many years’ lost opportunity for decent returns can devastate financial security. Fifteen years is something like 20% of the human life span, and far too long to watch a nest egg wither when it needs to grow to do its job. The closer you get to needing it, the worse the odds for recovery.

The Great Crash of 2008 makes the point even more painfully, and the 2000-2010 period represents America’s “lost decade” for investors, with the S&P 500 lower on the beginning of trading in January of 2010 than it was at the beginning of 2000. Of course, the markets have scored many records since, and by now this bull’s about tied (by the time you read this has probably surpassed) with the third longest bull market in history (numbers 1, 2, & 3, respectively, followed the 1987 crash, WWII, and the OPEC-bear market of the 1970’s). With risking stocks seeming to be a persistent, “natural condition,” many investors by now may have been lulled into believing happy days are here again, and forever.

Of course, that has never in history proven to be the case before, and probably won’t now. In fact, your risk danger alarm should be ringing.

I must stress again that I am talking about S&P 500-type US large cap stocks here, the names you know, blue chip, “conservative,” “safe” familiar stocks. There are many other attractive stock market opportunities – European blue chips are one of many to consider – the addition of several of which can help you both reduce risk and enhance potential returns.

I am not suggesting you pull out of stocks – with rates still low there are not many attractive alternatives anyway, and the studies consistently show that having a significant share of your wealth in stocks can prove the most profitable long term strategy, even for retirees and seniors living off their portfolios. I am suggesting that putting too much money on one type of stock – US large caps – can be akin to betting it all on one roulette number, and subject you to potential losses even as other stock asset classes do well.

In other words, diversify. I know you think you are, but I can tell you I regularly see portfolios we do stress tests on that have lots of names and positions, and hence appear to be well-diversified, when in fact all the ETF’s, mutual funds, and individual stocks add up to one dangerous conclusion – too much in US large caps! Just like in Case Study CPA, below.

Diversification is the father of risk control, but too few investors really have the kind that counts. The opposite of diversification is concentration – concentrating a lot of your wealth in one investment or investment type, the ill fortune of which can produce an enormous loss for you. Having a lot of different “names” – different stocks, mutual funds, brokers and advisors, whatever – is largely immaterial. You need to have pieces of markets that can be expected to move in different cycles, making it very unlikely that everything will go down together, like our friends in NASDAQ, or in countless other markets before it. We call these market pieces “asset classes,” and you want a mix that is poorly correlated, meaning they tend to move in different directions. For instance, the year that NASDAQ, the S&P 500, and other major US markets crashed, utilities were up something like 35%! Having other “pieces” like this goes a long way toward easing the pain and promoting financial health. Even after the Great Correlation of 2008 – a true black swan event where virtually everything moved down in the same death spiral – those investors with intelligent diversification fared far better, recovering losses much faster than those who were stuck in flawed programs or highly concentrated portfolios stuffed with CDO’s, or whose advisors made deer-in-the-headlights decisions which haunt them still.

But get this risk-control diversification right, and the bonus beyond downside protection is that you can reasonably expect to target superior risk-adjusted returns in the bargain! In other words, well-done allocation should actually cut risk and boost returns.

It is important for you to investigate these “concentration stress points” in your portfolio, and determine if you are overly exposed in one or several areas, like owning five different mutual funds that all invest in the same areas, and may even all have the same biggest holdings! You can do this using many tools, some you can subscribe to online, and determine the asset-class definition of each thing you own. Then calculate your individual asset allocation by seeing what percentage of each you have in your whole, to finally make a determination of what type of efficient, risk-controlled model allocation makes sense in your particular situation, to which you can compare your existing portfolio after evaluating each component and constructing a dollar-weighted composite of your own holdings.

If this seems more complicated than it seems on the surface, it is because it is. Just figuring out the existing dollar-weighted risk allocation in your portfolios is work enough. But finding an effectively risk-controlled allocation model that does not sacrifice performance can be the holy grail, for do-it-yourselfers and professional advisors alike, even for massive brokerage firms with colossal resources. Pretty pie charts are easy to make, and impressive “hypothetical” performance numbers touting yesterday’s winners picked after the race is over are simple to “achieve.” But finding an effective allocation framework that has stood the test of time can make for a long search, especially if you insist on a “real track” record based on actual results achieved for clients, instead of the “let’s make believe we knew the future x years ago and assume we bought the very best performers” smoke of hypotheticals, which really tell you nothing about an advisor’s investment skill.

Finding an effective model to control risk is absolutely critical, but the mismatches we have seen in the field from what investors actually own, verses what they think they own and what they should own, have been stunning. Building one yourself is possible, but will require a significant investment in study and practice, and more than just a little luck. Finding a quality model from an advisor who’s good – and they are out there – amongst the endless pie charts floating on the massive sea of investment mediocrity, can be almost as daunting a task.

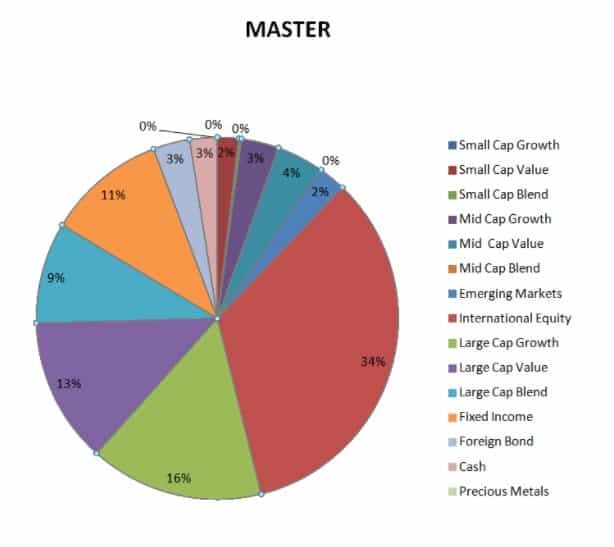

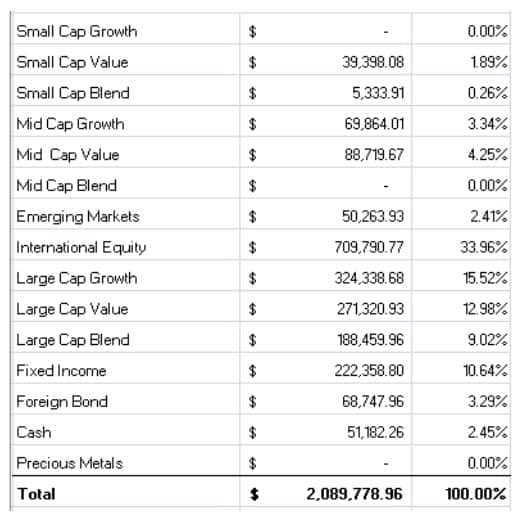

Case Study CPA

“James and Jane” are a fun couple. He is in his 70’s, and she is almost 60. They have six investment accounts, two IRA’s each, a joint account, and one account just in her name from an inheritance. Once of them is a CPA, and the accounts they held with their advisor seemed to be very well diversified. On detailed analysis – when we combined all positions in all accounts into one spreadsheet as part of our stress test, by researching each of the many, many positions and categorizing them into asset classes, then adding them up and graphing them as in in the spreadsheet and piechart below – a different picture emerged, as follows:

Almost 40% of the total allocation was in large cap US stocks, and 80% of the allocation to US stocks was in large caps. While the non-US allocation was reasonable, nearly none of it was in high potential growth areas like emerging markets, which include China (up about 40% so far this year as I write this), Korea, South America and other very promising areas. None of the non-US allocations were dollar-hedged, meaning that the strong dollar was eroding their potential profits significantly. Also, the fixed income allocation had a lot of junk bond funds when we dug deeper, which they said they did not know about.

It is important to note that the clients believed their advisor was working for only fees and putting them first, and they were quite surprised to learn that he was not in fact a fiduciary required to act in their best interests, and was taking commissions – some quite large but hard to spot – as well as fees. We find this situation to be quite common, and warn you that most “financial advisors” – including insurance agents, bank staff, and stockbrokers – are not fiduciaries, even though they appear to be – and you believe them to be – acting in your best interests. To be sure, insist that they tell you in writing that they are fiduciaries bound to put your interest first when managing investments.

There were other issues as well which we will discuss in the Case Study CPA sections to follow, and the cumulative effect was some pretty dramatic underperformance, which was so bad it will probably surprise you when we get to it. I stress that unless you are acutely tuned to it this can be very hard to spot – remember one of these clients was a CPA and used to financial analysis – but they still did not notice a very big difference from their growth and how well the market was doing overall.

They thought they were doing great, but sadly were doing quite poorly.

We should also note that while asset protection planning – techniques to outfox financial predators was very important to these folks, virtually none had been done by their advisor, with the result that a large portion of their wealth – well over a million in this case – was exposed to attack.

Danger #3: Are Hidden Costs and Concealed Fees “Robbing” Your Returns?

The accounting formula for profit is pretty simple: revenue – expenses = profit. In personal investing, it’s about as simple: gross returns – expenses = net returns. Keep your eye on the “net” returns, since this is the only part that is yours to spend, reinvest, and so on. If we assume for a given asset class that the gross return is constant – and for “classes” like the S&P 500 it is exactly constant – the only thing that can affect your net return is expenses. High expenses, bad. Low expenses, good.

Of course, you knew that, but it is sometimes helpful to be reminded, from time to time.

I know this seems pretty basic, but the differences in costs for the same fundamental investment class can be astounding. For the S&P 500 index, for example, one might pay as much as fifteen times more in a variable annuity than in an extremely low cost no-load mutual fund. For exactly the same core investment! The difference in your net return – the part you live and hope and pray and dream on – is pretty obvious.

Unfortunately, the differences in expenses between products is often far from clear, and worse yet, some vendors and salespeople actually seem to work hard to obscure the true costs, even if they are not outright deceitful about them.

It is unfortunate that getting straight info on some investment expenses can be quite onerous, even for savvy investors. Heck, it can take trained professionals hours or days to drill down and identify total costs on some products, if they can get all the information, which is sometimes practically impossible. Some may be found in the prospectus (which I know you read with keen interest), some in other documents you need to know about and ask for, like prospectus supplements, investment, wrap fee, advisory or annuity contracts, and the mountains of disclosure documents your bank, life insurance company, or broker is legally obligated to give you (but not legally obligated to make clear!) Some puzzle pieces which can cost you plenty you may never be able to get directly, like the markup (the slice the dealer takes over what it buys it for) you pay when you buy, or the markdown when you sell (the difference between what the dealer gives you, and what it sells it to someone else for.) Markups and markdowns for products like individual municipal and corporate bonds, by the way, are often amazingly expensive and complete off the radar of most investors. For mutual funds, the differences in costs between the “institutional” class shares favored by fee only advisors and the commission-and-expense laden “retail” class shares can be astounding and quite confusing since the name is often the same!

The ways you might overpay are legion. Many believe that the best way to guard against excessive or needless costs is to use an advisor, whose only compensation on investments is the fully disclosed fees that you pay for advice. In this case, the advisor should not have any fee-based incentive on investments other than controlling costs and making you money, since most charge fees as a percentage of your account size. The better you do – higher returns and lower expenses – the better they do, so the objectives are better aligned. This is in marked contrast to the commission model (most banks, brokers, and insurance agents/financial planners) and the investment “fee-based” model, also used with increasing frequency by many of the folks just mentioned. Fee-based investments compensation can be quite dangerous since the fact that fees are charged can obscure the other fact that commissions on investment sales are also charged – and in many cases, commissions make up the lion’s share of the advisor’s compensation on investments. Since many fee-based investments sales folks seem to work very hard to give the impression that they work on fees only, some confusion on the part of consumers is only natural. But be warned: only fee-only means fee only; fee-based means fees plus commissions, every time. Get it in writing, and make sure it is clear. “I work on fees…” can mean many things, many of them hazardous to your wealth.

As a sidebar to this section, remember that fiduciary advisors like (only Registered Investments Advisors are required to be fiduciaries, unlike most stockbrokers, insurance agents, financial planners, and bank reps) have a legal duty to put your interests before their own. “Suitability” advisors – the vast majority – are not. They put making money for themselves and their employers before you. If an advisor claims to be a fiduciary, get it in writing. Just because a product is “suitable” for you does not mean it is best for you! It can be amazingly overpriced, mediocre, and a poor fit for your goals, but still be suitable. Fiduciaries, on the other hand, must place you first and work to do what is best for you.

Case Study GPA

As part of this Portfolio Stress Test, we ran a Morningstar report on each position the couple had in each account. We use a professional version of Morningstar that produces very detailed information. Morningstar typically assigns star ratings from one to five, which we convert to letter grades F (one star) to A (five stars). We feel this gives a more objective impression of the relative rankings, and allows us to produces a GPA type score for the entire portfolio.

Besides the asset allocation problems we discussed above we found a lot of quality issues as well. For instance, there were twenty individual stock positions across all the accounts, with the following converted ratings: 0 A’s, 1 B, 12 C’s, 3 D’s, and 4 F’s. The “GPA” for the stocks was 1.5 – failing.

The mutual funds were a bit better grade-wise, but still pretty mediocre. In our report to them, we summarized as: “High allocation to mutual funds, of average ratings but most extremely expensive for mutual funds and doubly so compared to tax-efficient ETF’s; possible fee sharing with your advisor may explain this; these high costs, plus commissions and advisory fees, compound the effects of non-optimal portfolio decisions…” Virtually all of the funds had needlessly high expenses, a large portion of which were so-called “12-b-1” fees that are essentially ongoing “trail” commissions to the advisors, of which the clients (as are most investors) were unaware.

Also troubling were the presence of high-commission, non-publically traded REITS in some of the accounts. These commissions and upfront fees cost the clients as much as 10% of their invested capital, a major hit to overcome; unfortunately this commission cost is not clear on the statements and was not clear to the client. Perhaps worse, the non-public part means there is no active trading market for the REITS, which means it may be difficult or impossible to get their money back if desired. This is especially disturbing since many high quality, low cost, no-commission, completely liquid publically traded REITs are available, such as those used by fee-only portfolio managers.

Danger #4: Do You Miss Big Profits from Hot Sectors….Year After Year?

The rusty flipside to danger #4 – taking unnecessary risk by loading up on only a few asset classes – is that you tend not to own pieces of things that occasionally yield big profits. This is really a double whammy of sorts: having a poorly-crafted asset allocation not only increases your risk of losing money, but decreases your likelihood of making good money! From 2000-mid 2006, while NASDAQ slid to unprecedented levels that persisted for many years, some emerging asset classes, Russia for example, were up something like 650%! The same thing seems to happen every year, and in spades since the Great Crash of 2008. A robust, broadly-diversified asset-allocation model generally uses 8-12 distinctly different asset classes, or allocations of capital to markets expected to move in different cycles, at different times, and for different reasons. Every once in awhile, certain asset classes – like gold, real estate, oil, tiny companies, third-world stocks and junk bonds – can be expected to hit really big-time. Having just a sliver of these sorts of things can really make a difference in long-term portfolio performance, as well as helping to control overall risk. If your current holdings exclude them, for whatever reasons, the underperformance of your investment accounts is entirely predictable. Get a decent asset allocation model from a source you trust and compare it to your current allocations, kind of like we did for Danger #3, but this time looking for what may be missing, instead of what you have too much of.

By the way, the real magic here is in blending these different breeds of cats close to the “efficient frontier,” that elusive investments sweet spot expected to produce the maximum return with the least amount of risk. It is important to recognize that just having an allocation – even one with lots of poorly-correlated asset classes – is not enough. You need an efficient one, properly designed to increase the probability of upside and minimize the likelihood of losses. The actual efficiency of a proposed allocation – no matter how pretty the pie chart – is something extremely difficult to predict or measure, even for a trained analyst. Track records, though, speak louder than the most enthusiastic sales pitch. If you allow us to conduct the FREE Portfolio Stress Test™ for you, you can even see exactly how the ISIS® Portfolios have performed, and compare these results to your past investments experience, to try to get a real sense of how well your current accounts measure up. Of course, you may have a hard time actually getting accurate performance numbers from your existing advisor, as we have found that many make it extremely difficult to get this information, or simply do not provide it at all! They will give you “account value change” data from statement to statement, but not the net (after all cost), compound rate-of-return results that you really need to understand performance and compare to the markets and other alternatives. I suspect this is intentional, as a way of concealing high expense and poor performance, but I am a suspicious man. And remember, if it’s not in writing, it may just be a guess…or worse. We spend more time on this at Danger #6.

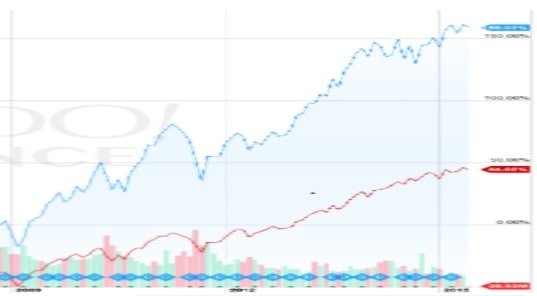

Case Study CPA

As we mentioned under Danger #2 when we reviewed the case study asset allocation, nearly 80% of the US stock allocation was in large caps; there was virtually none in US small caps. As can be seen in the graph below since the market bottom in March of 2009, this was an unfortunate oversight, with US small caps (represented by the blue line) handily outperforming the red-line S&P 500.

A more recent effect concerns the non-US allocation. There is nearly none in emerging markets, which we have mentioned we feel to be a big mistake. Also troubling was the fact that while there was a significant allocation to foreign stocks, the exposure was not currency-hedged during the recent period of US dollar strength; the short of it is that gains in non-US stocks were often canceled out by a rising dollar, with some periods actually showing net losses as the dollar went up more (making non-US stocks worth less in dollar terms) than the foreign markets. This could have easily been avoided with any number of dollar-hedged foreign stock mutual funds or ETF’s.

When we get to the performance discussion under Danger #6, you’ll see the devastating impact of these cumulative dangers on the couple in this case study.

Danger #5: Are Your Investments Right for Your Age? Do You “Give Up” Too Much?

This danger is going to seem counterintuitive, but your investments have nothing to do with your age! I know that flies in the face of conventional “wisdom,” but your portfolio should be set up based on your emotional risk tolerance – how well you sleep when markets go bump in the day – and your economic risk tolerance, the cash flows you are likely to need, and when, out of your nest egg. In fact, this second one – matching your portfolio to your income needs – is really the most important driver. Age, really, does not factor into this at all, and rules like “your equity percentage should be your age minus…” are just so much rubbish. Every day in practice, we see retired –and some far from retired – folks whose portfolios are paralyzed by these half-baked rules of thumb, and loaded up with so much cash and fixed-income that their probability of getting the growth they’ll need to maintain their lifestyle down the road – in the face of taxes and inflation – is seriously compromised. On the other hand, some younger folks we’ve seen take so much risk, in the name of “I’m young so I can be aggressive”, that the risk of loss and never accumulating enough to reach their financial goals is alarmingly high, if not a fate accompli. If we perform your free Portfolio Stress Test™, we’ll analyze this for you and let you know if we see any danger signs, and show you what we think the best portfolio match for your “age” and income needs is.

Case Study Doctor

This data is from a different Stress Test than the previous ones, which we conducted for a doctor hoping to retire in a few years at age 70. Despite being “advised” by a very well known “wirehouse,” the investment trajectory did not seem very promising. From our report to him:

“Note that virtually every bond (except GE) matures to less than purchase price – certain loss if held to maturity – and that the bond positions are about break even from what you paid at this point – but as rates go up losses will likely mount especially for some of the longer maturities; loss on all is certain if held to maturity, plus the opportunity/inflation cost as rates go up and you can’t pace them. Overall allocation is concentrated on fixed income and US large caps, both of which we forecast to do poorly going forward, virtually no allocation to non-US stocks to which performance baton seems to have clearly shifted (and which we feel are are generally much better values than US stocks). Again, because your broker sold you bonds at prices higher than the maturity value, they are sure losers if held to maturity, and likely to fall as rates go up if not. Overall allocation appears too concentrated and unlikely to control risk and produce the growth desired for your goals of robust inflation adjusted retirement income and substantial inheritance for your daughter. Your liquid retirement pool is $1.59M; your broker produced a pre-retirement growth rate 45K/(955K+370K)=3.4%; 2 years retirement on FV of 1.7M; 4% income load of 68K is shy of 120-40=80K net needed, and the research says 4% is pushing it for retirement only not including funding bequests. More appropriate investment management needed to increase probability of achieving goals.” The math is shorthand for saying that his income need, after Social Security, is such a high percentage of expected assets in the two years when he wanted to retire, that he will likely spend down his money well before his life expectancy, and not only be broke but not be able to leave the estate he wanted for his child. The alternatives – if he stayed on that investment course – are working longer, or comprising his desired retirement lifestyle.

The gist of our conclusion was that besides paying high markups and commissions of which he was unaware, the doctor’s investments were not likely to produce the growth he needed to have the retirement income he wanted, and the high percentage in bonds – which appears conservative on the surface – was not only inadequate to target the growth he needed, but actually pretty risky – with a high probability of loss – in the expected rising interest rate environment.

His investments are definitively not right for his age, and also suffered from many other correctable problems.

Danger #6: Reality Check – Have Your Investments Done as Well as You Think?

This is a tough one. We all want to believe we’ve done especially well, that the decisions we’ve made and the advice we’ve relied on has worked out for the best. Sadly, in the harsh light of the cold facts – which we often prefer not to face – this turns out often to not be the case, to our possible detriment and financial insecurity.

With the big run up since March of 2009, you probably feel like you’ve done pretty well. But have you outperformed the market? Have you even kept up with it? You may not be so sure…especially after you’ve read the case study box below.

We’ve learned from the field of behavioral finance – the study of how and why human beings make investment decisions, and why they often act against their own best interests – that people tend to believe that they have done much better than they actually have, and that they are often resistant to receiving and believing information revealing poor performance, since to do so implies that we have made a poor decision on which investments to make or which advisor to trust. This is kind of an “ostrich/shoot the messenger” syndrome, and it must be overcome if you want to maximize your wealth and security.

Now, I surely don’t want to make you want to shoot me! On the other hand, you must be able to objectively evaluate your investments’ performance, and you most likely do not yet have the tools to do so. Most investment statements – with their “change in value from the last period” reporting, give no clue as to actual performance, let alone relative performance against what the “markets” have been doing. As such, they can let you – and the advisors who are serving you – believe that you do much better than you actually are.

You need the sort of scorecard that professionals use. To get that, you need to know the “scores.”

The first is called Internal Rate of Return, or “IRR.” This gives the real percentage gain or loss on your money, on an annualized or other periodic basis. It tells how well YOU have been doing. The second is called Time-Weighted Return, or “TWR.” This tells you how well your advisor’s advice has done. The first factors cash flows – if you put money in at a good/bad time, it shows the performance reflecting your good/bad “luck.” The second factors out cash flows since the advisor has little influence over when you have money to put in, decide to make a change, or need to take money out, generally. IRR gives you your “score,” TWR gives your advisor’s “score.” You need both to tell how your money has actually done, and how your advisors have stacked up against what could have been done, by comparing them to established market indexes and the published performance of other advisors. To be accurate and honest – “transparent” is the industry term – they need to be presented net of all fees, commissions, expenses and other costs. They need to be for generally accepted periods like calendar quarters and years that you can compare to what’s been published. Most of the time, this information is never revealed on investment statements (or even available to your advisor) and beyond the reach of most folks (including too many investment professionals) to readily calculate. But you really need to know, if you want to shake the sand out of your eyes, and see if your nesteggs sit in the sun or the rain.

You can try to do this on your own if you have very good records of buy/sell dates, all costs and expenses, holding periods, reinvestments, and deposits/withdrawals. That assumes, of course, that you already know (or are willing to learn and remember) the calculus of investment performance. Do not forget that except in rarely-encountered situations, you cannot rely on your advisor to accurately track the data and present the analysis to you; most have no duty (and too many sadly have no ability) to do so, the “change from last period” stuff you see on your statements is nearly useless, and can paint a rosier picture (that we all want to believe) than is actually the case.

Fortunately, there is an easier way. If you take us up on our free Portfolio Stress Test™, we’ll do a lot of this for you, at no charge, if you ask us to and have some basic data to work with. We can look at your existing holdings adjusted for commissions, charges, and the like, and analyze how they’ve done over “apples-to-apples” assumed holding periods. Or we can look at account values over your data timeframe and infer the time weighted return. While the output is highly dependent on the quality of data you have been provided by past advisors, this exercise can still produce very valuable insight. We call this reality check your RealScore™ Performance Analysis™, and it is offered free to those who request it as a part of the Portfolio Stress Test™. As usual, the customized conclusions we’ll generate for you are yours to keep, and use in any way you see fit: on your own, with your current advisor, or with those you may interview to manage your accounts if you consider a change.

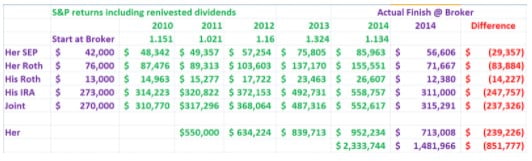

Case Study CPA

Returning to the case study we looked at before the retiring doctor story, the total of portfolio construction miscues – selection, expenses, commissions, ongoing management (or lack thereof) and – resulted in some pretty disturbing underperformance. Before we did the Stress Test, these folks – again, one of whom is a CPA – thought they were doing pretty well, but the reality is actually somewhat heartbreaking.

The spreadsheet below gives inferred performance for these client accounts based on the data they were able to provide. They told us there were no cash flows, so the beginning (Jan 1 2010 for all but one account) and the end values (Dec 31 2014) were clear. These are the purple numbers. In this case they asked us to compare performance to the S&P 500, so we took that annual return number (15.1% for 2010, for an appreciation factor of 1.151) to calculate “what if” values for each year in each account to emulate what the S&P 500 benchmark performance would have been. These are the green numbers. The bottom purple 2014 number ($1,481,966) was the total of their account values at the broker at the end of 2014, and the bottom green number ($2,333,744) would have been the total S&P 500 emulated value if that had been their performance. The bottom red number – $851,777 – is the difference between what they got and our hypothetical S&P 500 estimate. Nearly a million dollars difference in a five year span! Of course, this is not a rigorous academic analysis. For one thing, the data are too incomplete. For another, the investment asset allocation the broker had put them into did not match the S&P 500, but since this is such a popular benchmark, it gives some useful context.

Of course, this is not a rigorous academic analysis. For one thing, the data are too incomplete. For another, the investment asset allocation the broker had put them into did not match the S&P 500, but since this is such a popular benchmark, it gives some useful context.

These folks had thought they were doing far better than they did, and were pretty astonished to see the analysis above. They were also not too happy to learn about the commissions, mediocre rankings, and high expenses in many of their investments, and also to learn that there broker was not in fact a fiduciary who was acting in their best interests.

Your situation is probably somewhat different, and your available data may limit the observations we might make, but I can tell you the above situation is by no means unusual in our experience. If a CPA missed the big performance gap we noted above, is it possible you may have too in your portfolio planning?

Danger #7: Assuming your advisor’s an expert…or puts you first

Financial advice is one of the most mystifying services consumers purchase. In a field which has evolved to become as complex as medicine, it remains very difficult to tell the difference between highly trained, ethical and effective advisors, and charming salespeople who may or may not be able to effectively grow and protect your family’s wealth. Hopefully, this section will help to clear the mystery and share some easy guidelines to ease your decision, and help determine which advisor can best suit your needs, and whether your existing advisor makes the grade, or if you should consider replacing them.

We believe there are three critical factors, which we call the 3 Keys to a Great Advisor. They are:

- Education, training and expertise

- Minimized compensation conflicts of interest

- Requirement to put your interests first

All are critical to getting excellent advice. A big mistake, of course, could be using an advisor who is deficient in one or more of them, since the absence of even one of the 3 factors can lead to financial underperformance or even disaster.

Before we get into the factors, it is important to mention that the term advisor – which used to have a stricter meaning and was reserved for professionals who had a legal duty to put clients’ interests first – has been transformed into more of a marketing term, now applied to what we used to call stockbrokers, insurance salespeople, bank staff, and others in sometimes misleading ways, even using commercials which seem to imply they must put your interests first, but actually mean no such thing.

Education Perhaps surprisingly, it is very quick and easy to become a financial “advisor.’ The government licenses required can be obtained quite rapidly, with very little depth of study or knowledge required. Regulatory agencies – the States and the Federal government for securities (stocks, mutual funds, etc), and the States alone for insurance (including life insurance products and annuities) – require only fairly simple sales licensing exams which can typically be passed by a person of average intelligence with just a few weeks’ preparation. For instance, I was able to pass the Series 7 “full service stockbroker” exam – much more complicated than the Series 6 license common with many advisors today – the first time, cold, with only a week’s worth of study, and no background in finance (in fact I had a recent degree in chemistry). The Florida life insurance license required two weekends of classes. This kind of license does not connote much knowledge or expertise, but merely the legal permission to sell products, usually on commission.

To my mind, the first basic step on the long road to financial expertise is the Certified Financial Planner™ (CFP®) or the Chartered Financial Consultant® (ChFC®). These programs are roughly equivalent and teach the basics of financial planning fundamentals – financial planning procedure, investments, income tax, retirement planning, estate planning, and insurance/risk management – which must be refined and internalized with later, more advanced study. These basic “letters” are bachelors of sorts for the business, though it is interesting to note that neither requires a degree – or even any college credit – in financial planning studies. As of January 2015 web search, there were 629,500 people with securities sales licenses in the US (http://www.finra.org/Investors/ToolsCalculators/BrokerCheck/P015174) and only some 71,400 CFP®’s (http://www.cfp.net/news-events/research-facts-figures/cfp-professional-demographics), or about 11% of securities licensees having the CFP® basic credential, when one considers the number of insurance agents offering financial planning who do not also have a securities license, the percentage drops still lower. My point here is not that I think having a CFP® or ChFC® qualifies an “advisor” to be an investment expert – I don’t – but that so few licensed investment salespeople have even this basic credential. I think advanced investment training only begins with programs like a Masters in financial planning, or focused investment credentials like the CFA® (probably the hardest, most comprehensive, and most respected), the CMT™, or the CIMA®.

Compensation Conflicts The next concern is how to minimize compensation conflicts of interest. Even to this day, most investment “advice” delivered in this country actually boils down to commissioned sales pitches of financial products. Some products – like municipal bonds, annuities, non-publicly traded REITS and other investment partnerships – can carry huge commissions that are very hard to spot, and frequently not very well explained or even disclosed by the sales agent. For instance, on annuity sales it’s not unusable, if commissions are inquired about, to hear the agent say “well, you don’t have to worry about that, since I’m paid directly by the company.” And while this is technically true, it is very misleading, since while there is no obvious upfront commission, if you decide you want to get your money back you may typically pay a “surrender charge” of 8% or more which amounts to a back end load or commission that primarily exists to fund the salesperson’s commission – which, typically, is roughly the same percentage as the 1st year surrender charge (8% in this case or $80,000 on a million dollar annuity). We’ve seen fees on annuity products approaching 5% a year, by the time you add up all the subaccount, rider, mortality, and other charges. The surrender charge exists to allow the issuing company to recover the commission if you don’t stick around long enough to pay for in out of the annual charges and still allow the company to profit. Obviously, with commissions, the more the sales rep makes, the more comes out of your pocket, and the lower the net value of the product to the buyer. There is no magic here, despite the smoke and mirrors that may be trotted out. That’s the reason for the saying that high commission products are “sold, not purchased.” We believe that a fee-only approach – no commissions, just a straight small percentage that is typically lower than the internal product costs in many annuities, for instance – is a better way to align our interests with those of our clients, since we have no motivation to recommend any investment other than on its merits, and since that way, the better the clients do, the better we do.

Requirement to put your interests first Finally, we think it’s critically important to work with an advisor that’s a committed fiduciary, and required to put your interests first at all times. Most investors believe this is the case with their advisors – and the advisors don’t seem to do much to correct the misunderstanding – but are often sadly mistaken (see case study box below). This is so important, and so easily “misunderstood,” that we strong encourage you to get a pledge in writing that the advisor will act as a fiduciary and put your interests first when advising on investments and related matters, and when actually managing money for you. All the time, not just on some investment products, as is the case when a stockbroker, for instance, can act as a fiduciary with RIA products on some of your money, and sell you high commission products for the rest of it.

One final tip: if an advisor works for a bank, brokerage house (Dean Witter-type companies), insurance company, or large financial planning company with extensive national advertising, they are almost certainly not acting as fiduciaries, or are even allowed to. This can be an obvious red flag if you are looking for a fiduciary. Harder to identify are those advisors – like the one in our case study below – who “private label” themselves as “John Smith Financial” or “ABC Advisors,” even if as they are acting as commission sales agents by being stock brokerage representatives (“registered reps”) or life insurance product representatives. The disclosure documents can reveal this, but they can be tedious reading, and some speculate they are intentionally written to be a little confusing, or even intentionally misleading! Simpler, I think is to ask for a written declaration of how and advisor is compensated, and if they are acting as a fiduciary in all matters when dealing with you. A simple one page statement on the advisors’s letterhead ought to do it, and if you can’t get this you should be suspicious. And don’t rely on designations like Certified Financial Planner (CFP®), CFA®, or others to infer fiduciary statues or compensation method – these tell you nothing about compensation, commissions, or fiduciary status – just what training a particular advisor has completed. There are scads of non-fiduciary annuity sales agents who hold the CFP® mark, for example.

Case Study CPA

From our Stress Test report:

“Relationship (fiduciary/suitability) and compensation/total costs of advisor is unclear but of high concern. Has what you pay ever been clearly explained, in writing? There are troubling illiquid, probably high-commission products like XXX&YYY (His IRA), ABC (near all of His ROTH, and in Her ROTH). Mutual funds, of average ratings but most extremely expensive for mutual funds and doubly so compared to tax efficient ETF’s; possible fee sharing/commission splits with investment advisor could explain this. These high costs, plus any commissions and advisory fees compound effect of non-optimal portfolio decisions.

The advisor uses Firmname, which is really a wholesale platform for independent reps like Mr. Advisor. It is really a very small operation, just him & two administrative assistants. Have you checked his succession plan? He must be nearing retirement having started his career in 1975. While Mr. Advisor does have several basic life insurance industry-related financial planning designations, as well as the “Accredited Investment Fiduciary (AIF), he does not have any actual advanced investments training; it is somewhat ironic that his AIF (which can be obtained in three days) contains the word fiduciary, but he does not appear to be actually acting as a fiduciary…”

This section of this case illustrates several pitfalls – commission compensation having the high potential to drive a big wedge between clients’ interests and the advisor’s, the lack of fiduciary status letting the advisor’s interest dominate and possibly damage the results for the clients, and the AIF credential that possibly implies more training than the three days cited by Investopedia (http://www.investopedia.com/articles/professionaleducation/07/aif-aifa.asp). Given the bewildering array of financial designations and “letters,” it is difficult to know which actually represent significant study and achievement. In my view, the CFP®, ChFC® and CPA/PFS® are good basic planning credentials, and the CFA®, CIMA® and CMT™ are respectable investments credentials, with the CFA® probably considered the most respected. More information on several of these credentials can be found at the end of this report. Advanced degrees – Masters or Doctorates – in related fields (but not just in business) are also worth notice.

Danger #8: Buying or Holding Bonds at the End of a Low Interest Age

Buying bonds is traditional considered a low risk investment activity, especially where highly-rated or US government bonds are concerned. The reason is simple: buy a bond from a solid source, and there is a very high probability that you will get what it promises – interest payments on time, and your money back when the bond matures. This “low risk” argument has always ignored two crucial factors, those being taxes, and inflation. When the toll that these two stealth risks take are tallied up, many bond investments produce net losses to their owners, in terms of purchasing power. There is a net decline in value in terms of real wealth. While this is not true for all investors in all markets, it is true often enough to be a cardinal rule to be remembered by all investors.

As we face the end of the near-zero interest rate era in the late twenty-teens, there is a very special case of this rule that looms as a disastrous risk for modern investors, driven by today’s low rates, and the current high risk of very high inflation. Both of these are a direct result of the “printing press” expansion of the US money supply, in the wake of the Great Recession. While these policies probably prevented a more severe contraction or even a Depression, these artificially low rates can’t hold forever without risking a very nasty surge of inflation, the likes of which has not been seen since the 1970’s in this country; even with rising rates, inflation is likely to be a much worse problem than it has for decades. Bear this in mind, as your mindset is probably not well prepared for this, having got used to low inflation for decades now.

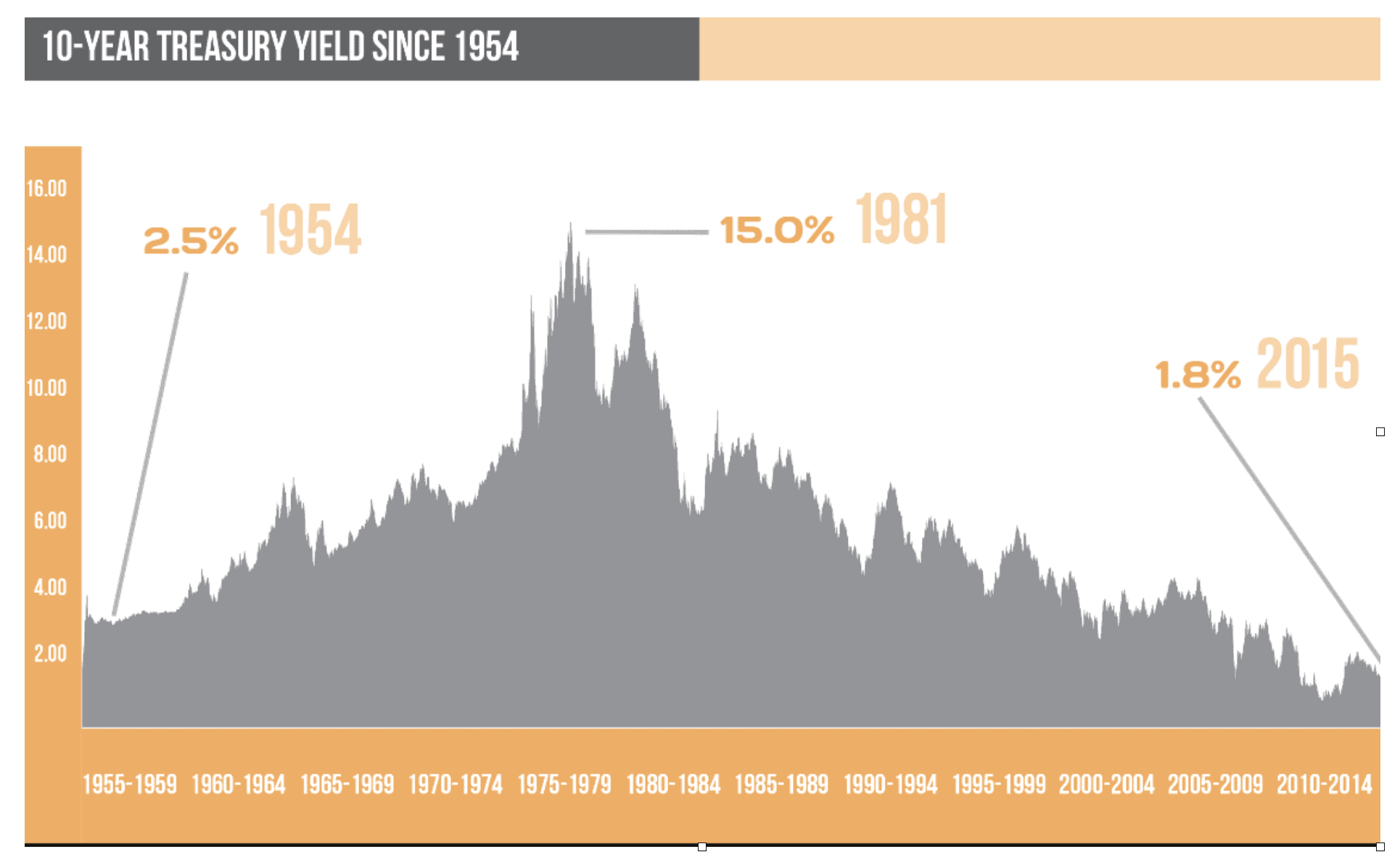

Worse yet, all of this sits on the powder keg of a likely bond-market bubble that has been building for thirty years. Have a look at the following graph, which charts interest rates on the US 10-year note. Bond prices move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Of course, most of us know intuitively that interest rates are very low now, and seem to have been falling, more or less, for a long time – since the high inflation days of the 1970’s. What is less obvious is that bond prices – which move in the opposite direction from interest rates – have been rocketing up for just as long, to levels that many fear have reached unsustainable “bubble” valuations. From the graph below, rates have been dropping since the late 1970’s, and bond prices have been rising since then, and now sit at near 40-years highs. When rates snap back – as they gradually did from the mid-50’s to the mid-70’s – bond losses, especially on longer term maturities, could be severe.

The short of it is that bond buyers/holders today face a huge problem beyond miniscule interest rates…the risk that values may tumble disastrously – in a macabre echo of the 2008 Stock Crash – if interest rates rise. For example, for a bond maturing in 10 years paying 2%, the value can drop by more than half if rates go to 12%…a million dollar investment could plunge to a market value of less than $450,000 in this simple example. There is more to it than that, of course, but this should make the big risks of buying bonds in a super-low interest rate environment quite clear. Note that this risk extends to market-adjusted (“MVA”) annuities and other “guaranteed” investments of the sort. The longer the term to maturity, the greater the risk of principal loss is. And while bond owners often take false comfort in their ability to hold until maturity and so get “all” their money back, the reality is that in doing so they miss the opportunity to invest at much higher interest rates along the way, and the loss – the true economic cost – turns out to be just about the same.

The other big risk to consider is default, the risk that the bond issuer will stiff you and not pay your money back. One must watch ratings carefully and regularly, and take them with a grain of salt. Remember that the “toxic waste” mortgage bonds that precipitated the Great Crash of 2008 came with investment-grade ratings, but turned out to be higher risk than junk bonds? Finally, note that bond funds are as exposed to these risks as individual bonds.

The short of it is that “conservative” bond investments may actually be quite risky in a risking interest rate environment, and that this risk is particularly acute in the mid-twenty-teens. It is difficult to overstate the potential magnitude of this risk in terms of purchasing power erosion, running out of money, or suffering big losses you may never be able to overcome. See the Case Study box for more detail. And, as an additional word of warning, many annuities have values tied to the bond market, and these risks affect them to varying degrees as well. If you have us do the below Stress Test, we can also help you assess any hidden risks in your annuities, if you have them.If you have (or are considering) bond positions, we will give you an objective evaluation as part of your free Portfolio Stress Test™, if you ask us to. If you are heavily into bonds, I cannot overemphasize how important I think assessing this risk is, and how dangerous to your financial security it could be.

Case Study Doctor

The doctor looking to retire in a few years was running a double risk with his large municipal bond holdings – not having enough growth to generate the retirement income he wanted and possibly running out of money, and the risk of actual losses on his bond holdings as interest rates went up.

As discussed above, he had “lost” a good bit to bond markups when he purchased the bonds, a fact he was unaware of when he bought them. Markups are a poorly understood method of compensation to commission advisors and brokerage firms, but really no different from other retail products like tires or canned goods at a grocery store – if the wholesale price on a can of peas is $1.00, and a store retails it for $1.25, the markup is 25%. That’s an exaggerated example and bond markups are not typically that high, but you get the point. While most investors are oblivious to this – believing that the price they pay is what the bond is actually worth, the reality on the other side of the phone is somewhat different. According to a story about a stockbroker selling bonds which appeared in the New York Times: “I saw the sales process firsthand when I worked for a large brokerage firm in the mid-1990s. During training, I often asked grizzled veterans what advice they had for a rookie. I was particularly curious about how we were supposed to decide which bonds to buy for a client’s portfolio.

The answer I got more than once was something like, “Go to the list of bonds we keep in inventory and see which one pays you the most.” So instead of seeing which bond would be best for the client, I was supposed to figure out which one had the highest markup and would deliver the highest compensation for me and the firm. I could actually adjust my commission up or down without the client really having a clue.” (http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/17/your-money/determining-the-markup-on-municipal-bonds.html?_r=0).

Again, this underscores the little-appreciated fact that many, if not most, financial advisors are looking out for their own interests, not yours.

In the case of the Doctor, he actually bought most of these bonds at a “premium” – in other words, he paid more to buy them than they would mature to. Holding to maturity would actually produce a loss over what he paid. He did not know this and was pretty shocked when I pointed it out to him. Moreover, he had low interest “tax free” municipal bonds, but was not in a high enough tax bracket to make these pay off – he would have made more net interest with corporates. Even worse, with him planning to retire soon – when his tax bracket would plunge – and the lower interest rate from munis would hurt him even more.

With rates already headed up when we met him, the losses on his bonds were getting worse, but fortunately not yet so bad that he might be doomed to working forever or sharply cutting back on his desired retirement lifestyle.

The major point here is that during the best of times larger allocations to “fixed” investments like bonds, CD’s, and fixed annuities risk profound underperformance – lack of meaningful, “real” growth – after taxes and inflation. In the worst of times (rising interest rate environments, which we believe will be the status quo for years to come), the potential losses might be viscous.

Danger #9: Ignoring Taxes in a Confiscatory Age

This last danger has been sneaking up on this country for a half-century, widely noted but widely ignored, and the time of reckoning is upon us. Taxes are going up, big time. This is not only a result of the social initiatives, massive Great Recession bailout, and militarily costs of the early 21st century, though they have exacerbated the problem. The big issue is the old “third rail” of American politics, Social Security and Medicare, and the long-predicted population trends that will drive both deeply into the red, and soon. While the ultimate fate of Affordable Health/”Obamacare” is uncertain, it is certain that the associated costs will both exacerbate the deficit and increase taxes in many ways, not the least of which is the new “Net Investment Income Tax” on top of regular capital gains and income taxes in many cases. From a planning perspective, the reasons really don’t matter. What does matter is that proper tax planning is becoming a much more crucial part of intelligent investment planning, and can make a huge difference in how much of your wealth you keep. As the saying goes, “it ain’t what you make that counts, it’s what you keep.” There are a host of effective tax control strategies available to today’s investor, from legal “wash” sales and efficient loss harvesting to proper matching of investment type to account type – capital gains assets, for instance in taxable (where they get the lower capital gains tax rate) instead of tax-deferred/IRA accounts, where they do not (and pay the highest marginal rate regardless; for interest-paying investments, the opposite is generally true. As in most things, those with the best advice and planning tend to pay the least tax, and the higher tax rates go, the greater the differences in wealth between the best and poorest informed. If you take advantage of your free Portfolio Stress Test™, we’ll happy to share tax insights that we have developed to more effectively keep clients’ wealth in their pockets. We can probably give you a few sharp tax control ideas to use on your existing portfolio, which could help you tax-manage your investments to a much better overall result. This tax risk has really become quite profound, given the political turmoil and intense fiscal pressures of the twenty-teens. This environment presents many dangers, but also many opportunities for the nimble, as tax law changes and morphs. We hope that you will allow us to offer some guidance to help you grow your wealth through these challanging times.

Case Study CPA

For our last case study observation we return to James and Jane. As we conducted their Stress Test, we were quite surprised to find that besides other apparent portfolio management deficiencies, excessive taxable income – I mean a lot! – was being realized for no apparent reason. This was especially troubling since Jane was still working and earning a high salary, putting them in a high tax bracket.

For the prior year, her non-IRA had $31,000 in interest/dividend income, and $60,000 in capital gains; the joint account had $12,600 in interest/dividend income, and $21,000 in capital gains. The total additional taxable income the advisor saddled this couple with was some $126,000 – on top of their other professional, pension, and James’ Social Security income! This produced needless additional tax of some $30,000, most of which could have been completely avoided had better (or some?) attention been paid by the advisor to tax management.

I wish I could say this was an isolated situation, but it is all too common – worse yet, typically unnoticed by clients (even this CPA client!), their financial advisor, even their tax preparer. But the needless drain on their wealth was real, and unchecked until we did our Stress Test.